NHS England has now published, following public consultation, a final interim service specification for specialist gender incongruence services for children and young people.

The public consultation on this draft interim service specification ran for 45 days from 20 October to 4 December 2022. It received 5,183 responses in total.

Our Duty has previously set out the following criterion for the success or failure of any policy development:

“Does the proposed policy meet the requirement for children and adolescents to be safe from the risk of unnecessary medical harm resulting from transgender ideation?”

This is a simple test. We can apply it consistently to all developments and announcements.

The new Service Specification fails this test. Our longstanding advice that NHS is not safe for children and young people with transgender ideation remains in place.

Key observations:

- Puberty blockers have not been banned.

- Young adults 18-25 are failed.

- There is backtracking on the use of ideological language.

- Dangers of Social Transition not fully appreciated.

- With no scope for consensus, the rational voices are ignored.

- The Cass Review is just “the political long grass”

NHS England commissioned TONIC – an independent organisation specialising in public consultation, social research and evaluation – to conduct analysis on all responses and report back on these findings.

Puberty blockers have not been banned.

At the same time as publishing the final interim service specification, NHS England also published a new draft interim clinical policy on the use of puberty supressing hormones (PSH) in children and adolescents who have gender incongruence or gender dysphoria.

This document, which has been issued to stakeholders like Our Duty prior to wider consultation gives a clear indication as to how NHS England is handling the issue of Puberty Suppressing Hormones (PSH). It is this document which demands attention as it is indicative of the direction of travel. From this draft clinical policy it is clear that, contrary to the claims of many observers, puberty blockers have not been banned.

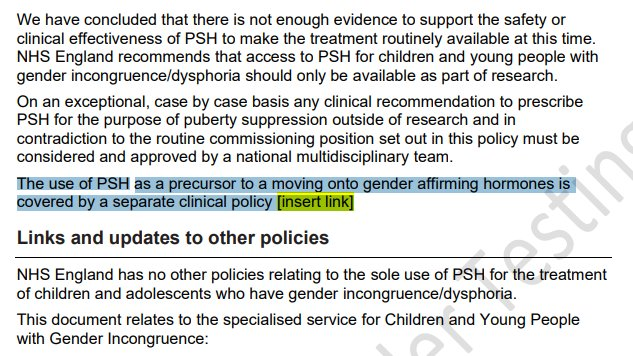

From the draft interim clinical policy on the use of puberty supressing hormones (PSH):

So, there are three ways in which a child can be prescribed puberty blockers under the proposed new regimen:

- As part of research – note that experimenting on children might be acceptable when seeking new treatments for childhood cancer, but when there is nothing physically wrong with a child, experimenting on them is right at the extreme end of unethical. This really does need calling out.

- On an “exceptional, case by case basis” – who knows what this loophole is designed to accommodate, but there is a tradition of loopholes like this being exploited and enlarged.

- As a precursor to moving onto cross-sex hormones. This is the practice, common in adolescent opposite-sex imitation, whereby puberty blockers are used to smooth the pathway from a balanced endocrine system with endogenous hormones to an imbalanced endocrine system with exogenous opposite-sex hormones.

The presence of this third clinical policy (the link is unavailable at the time of writing), alongside the other two ‘exceptions’, is indicative that, contrary to enthusiastic claims by some, the NHS has not “banned puberty blockers” at all.

YOUNG ADULTS 18-25 are FAILED

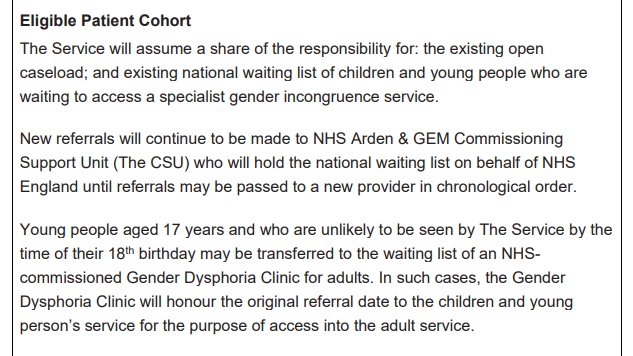

The upper age limit is set at 18 which is both inconsistent with the science and with NHS Long Term plan for delivering adolescent mental health services (which will bring the upper age to a sensible 25).

The failure to extend any duty of care to older adolescents is looking more and more untenable as the evidence mounts of the effects of medical malpractice on those over 18 with transgender ideation. Both young women and young men, and their parents, are telling their stories.

THere is backtracking on the use of ideological language

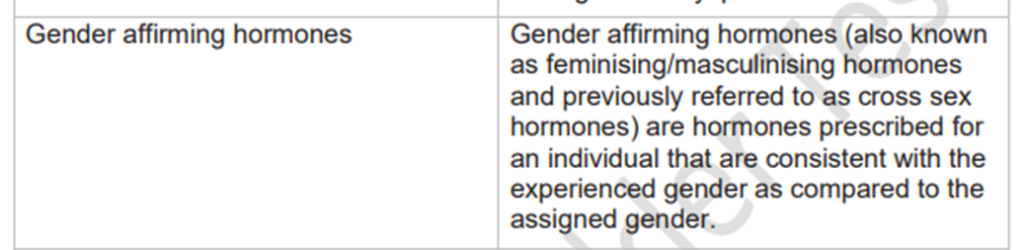

“The approach for onward referrals to endocrinology clinics are described in separate NHS England clinical commissioning policies for puberty suppressing hormone treatment and gender affirming hormone treatment.”

from the NHS Interim Service Specification

The replacement of “cross-sex hormones” (accurate) with “gender affirming hormones” (ideological) is a clear indication of the direction of travel, and it is backwards.

Phrases such as ‘assigned gender’ are used when the word ‘sex’ is perfectly adequate and free from ideological bias.

DANGERS OF social TRANSITION NOT FULLY APPRECIATED

Social transition as a part of a clinical intervention

Social Transition in the Interim Service Specification

Social transition is something that should be led by the young person with family input.

For the purpose of this interim service specification the reference to ‘social transition’ is intended to refer to the support offered by NHS clinicians to children, young people and their families who have decided that the child or young person will present in public fully with a gender identity different to that of their natal sex in all forms and aspects of their daily lives – rather than less profound forms of gender diverse expressions, behaviours or interests such as engaging in activities or presentations socially defined and typically associated with another gender presentation.

The ability to express individuality – and autonomy to change and adapt that expression over time – can be important to a child or young person’s development of the self and to their overall wellbeing. However, due to the social and psychological implications that social transition may have, advice about social transition should be seen as informing a significant decision when it forms part of an individual’s care.

While there are different views on the benefits versus the harms of early social transition, it is important to acknowledge that it is not a neutral act – and that information is needed about long-term outcomes to support decision making. Information and discussion about this with the MDT is an important part of supporting a child or young person in The Service.

As with much of the NHS approach to the challenges posed by transgender ideation, there is a recognition that there are opposing points of view, yet no attempt to establish which one is correct. There is no need to await a peer reviewed academic paper to conclude that ‘social transition’ is a bad thing. It can foreclose identity exploration, it vastly increases the risk of transgender ideation persisting into the territory of excess rumination and desire for medical interventions. These things are known. Social transition is to be discouraged at every turn.

In particular, the phrase “Social transition is something that should be led by the young person with family input.” gives great cause for concern. There are clear cases when the child needs protecting from the misguided behaviours of parents. Such behaviours might be ideological, come from poor advice (e.g. Mermaids), be Munchausens by Proxy, or just innocent ignorance. Whichever fault the parent might have, a foundational principle that all social transition is something to be prevented, discouraged, or reversed, is demonstrably necessary.

With no scope for consensus, the rational voices are ignored.

We are very disappointed that none of the recommendations we made in the public consultation were taken on board for the final specification. We consider this a dangerous and neglectful dereliction by NHS England. Every single suggestion that we made was objectively justifiable for the protection of children and adolescents.

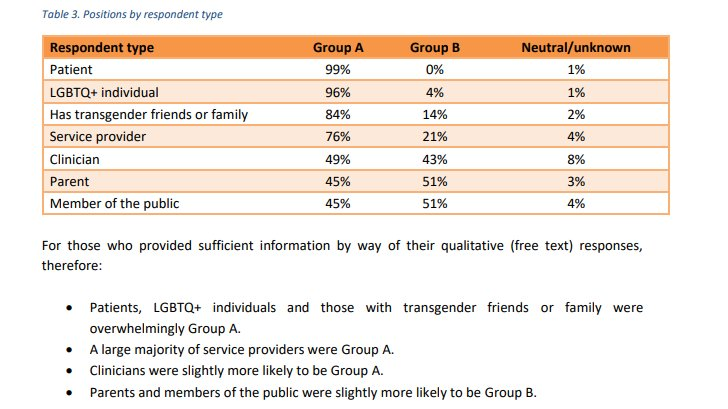

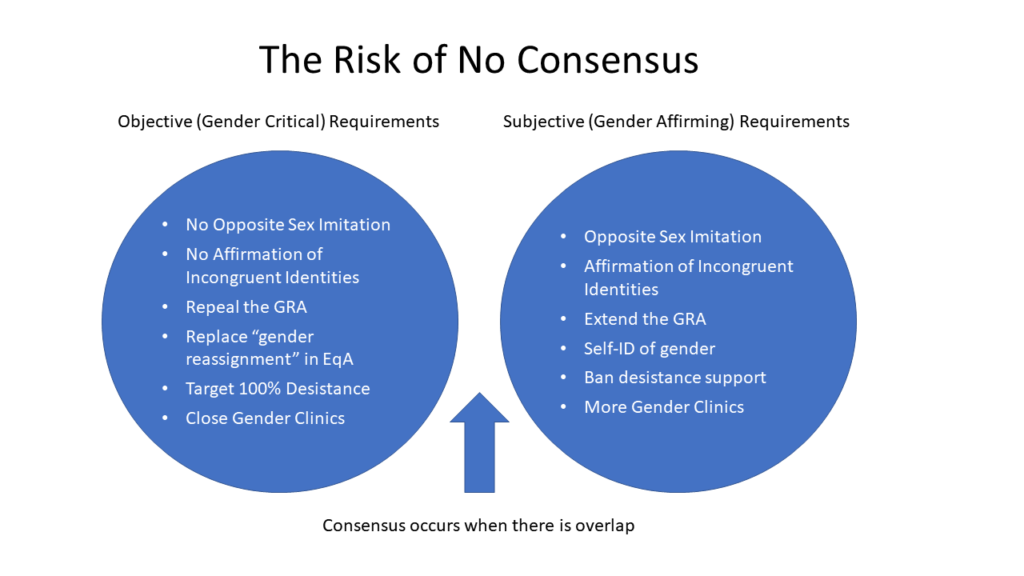

The TONIC report analysing the responses to the public consultation on the draft interim service specification brings into sharp relief the impossibility of consensus. With ‘Group A’ being in favour of medicalising transgender ideation and ‘Group B’ being opposed to it. These groups could be classified as “Give Patients What They Want” versus “Give Patients What They Need”. There does not appear to have been any weighting given to rational views over the emotional. Detransitioners – who have the knowledge and experience that should be given the most weight, were conspicuous by their absence. Future consultations should commit to seeking out the most important voices and giving their views appropriate weight.

It would seem from the final Service Specification that ‘Group B’ voices were ignored in favour of the ‘Group A’ voices. This was a grave error, yet consistent with the entrenched malaise within the whole NHS.

We have written previously about the ideological capture of the NHS.

The Cass Review is just “the political long grass”

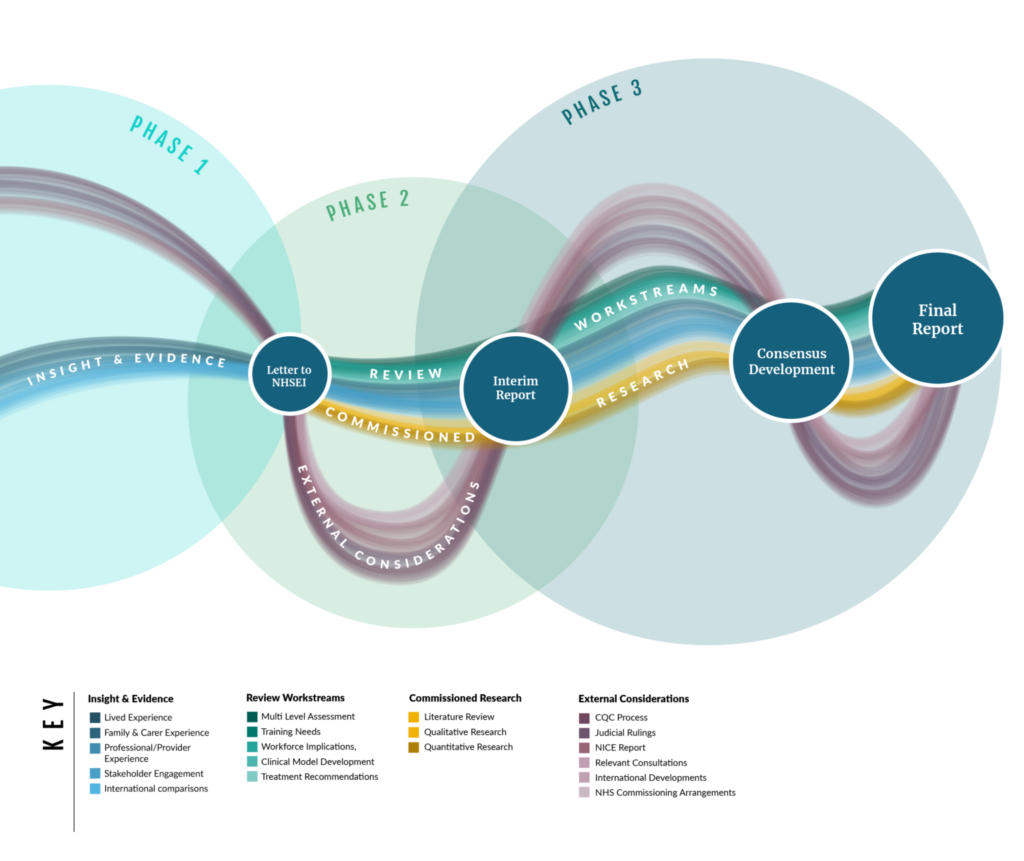

When The Cass Review published its terms of reference we encouraged parents to engage with the review on an individual basis. Our Duty was initially excluded from the consultation with only more moderate voices invited to represent parents. This was an early warning sign, along with words that implied a search for consensus, that any such consensus was to be artificial. It is clear to any observer of the debate around objectivity versus gender identity ideology, that there is no common ground. Consensus is impossible. We pointed this out.

The Cass Review was first mooted in the Autumn of 2019, those with concerns around the medicalisation of children in the name of gender identity ideology have now been distracted by the false promise of an objective review for nearly four years. This has been a classic example of politicians providing a sop to quieten dissent while absolutely nothing of any value happens.

Children and adolescent adults in the UK deserve better. Every day (on average) that opposite-sex imitation is still provided to this vulnerable cohort, a young person suffers irreparable harm.

Rather than seeking an impossible consensus, what our children deserve is strong leadership with a bias toward safeguarding and objectivity.