For decades, researchers and psychologists have recognized that the levels of “insistence and persistence” of gender dysphoria in children are important factors to measure. These experts have identified what most wise people instinctively know: there is a difference between a child’s temporary (and entirely appropriate) self-identification as a cat or Batman, and an extended commitment to a belief, identity, or activity, such as a child who practices basketball alone everyday past dusk for years.

Researchers, psychologists, and wise parents understand that there is a difference between a child’s temporary interests and life-long passions. We understand that there can be an extended “gray area,” between these two, too. Just ask any parent of a gymnast, ice-skater, or ballet dancer. It can be very hard to know. None of us want to crush our child’s dreams, but you ought to have some pretty strong signals and clear advice from the experts before you uproot the family to move to the closest Olympic training facility.

When it comes to childhood gender dysphoria, researchers, child psychologists, and wise parents also recognize that the vast majority (85%) of children with gender dysphoria desist around puberty – and that most of those desisters end up as gay or bisexual. Evidence shows that the 15% of children who do not have their gender dysphoria resolve were the ones who were the most persistent and insistent to start with.

In the past, gender dysphoria was an extremely rare issue – mostly affecting young boys and middle-aged men. Today, the largest group presenting with gender dysphoria are teenage girls. Most of these teenagers are rapidly developing gender dysphoria out-of-the-blue and out-of- character, having never struggled with this issue before. Something is going on.

The research on the causes and appropriate treatments for this new ROGD cohort is extremely thin. Nonetheless, the medical field in the United States keeps trying to apply the old treatment models (developed for those 15% of persistent/insistent young boys and the middle-aged men) to these teenage girls. (The U.K., Netherlands, and Sweden have all acknowledged the issues and the failings of that model, and have pulled back.) There is a bias and assumption that every case of a teenager with gender dysphoria is a “true trans,” despite the lack of evidence of childhood gender non-conformity, or the role of comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, Autism, and peer group dynamics.

Within our group of parents of sons with Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria, I have noticed some patterns in the development, progression, and resolution of gender dysphoria. The main one: the farther a person has gone down the path of social, medical, and legal transition, the farther they have to walk back. The ones who are least persistent/insistent and have made fewest changes can desist more easily. This is not rocket science. The more something grows, the bigger it gets.

However, to know how big or small something is, you need to have a measuring stick. So far, there appears to be no measuring stick for ROGD. Without a shared vocabulary for discussing the stages of ROGD, we cannot properly develop treatment for the different stages.

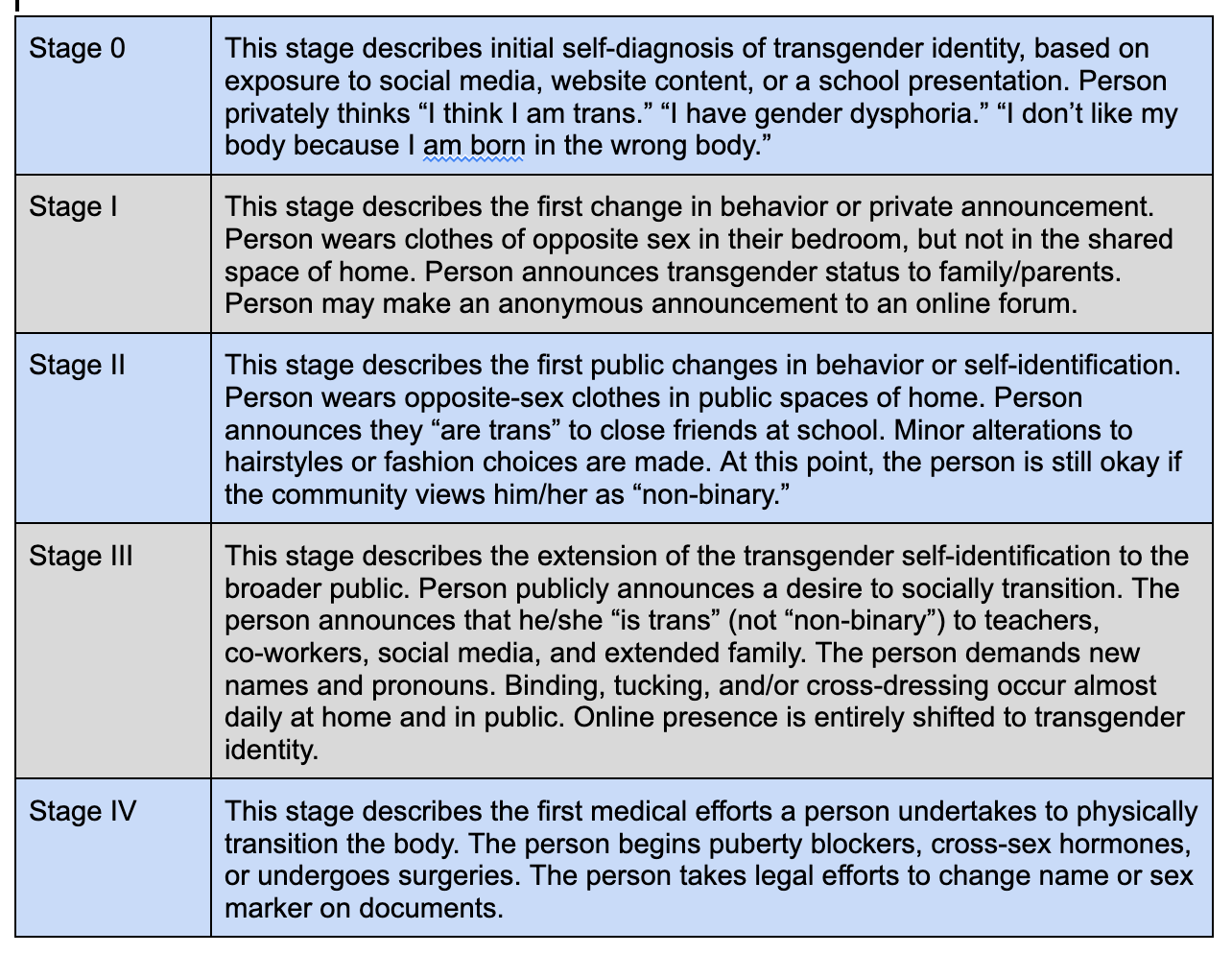

So, I propose the following definitions. A few caveats – these stages are intended for describing people who are experiencing Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria – these are not helpful for describing the previous/traditional presentations of gender dysphoria (childhood onset or middle-aged men). Also, these stages do not always occur consecutively or completely: a person may jump from Stage 0 to Stage III. A person may demonstrate some of the characteristics of a stage but not all.

Note that a clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria is not included in any of these stages. These phases are based on identifiable actions or behaviors, not on feelings. These phase descriptions do not serve as tools to diagnose gender dysphoria. Rather, they are intended only as measurement device to help parents and therapists observe and communicate the stage of behavior that a person is performing. “My son displays Stage III behaviors on the ROGD scale,” not “My son is Stage III trans.”

This isn’t perfect, but it’s a start.

With this language, I can now say that my own son announced he thought he was trans (Stage I) in June 2020, and stayed in Stage I until April 2021. We’ve observed no behavior since then, and believe him to be desisted. Courage!

By Donna M.

Originally published at https://pitt.substack.com/p/rogd-phases-time-for-some-definitions reproduced by kind permission.